The Stationers' Company: 600 Years of Printing

- Frances Beebe

- Nov 11, 2024

- 7 min read

Updated: Sep 10, 2025

How This Enigmatic Organization in London Held a Monopoly Over Publishing for Centuries

Image from an Almanac printed by Stationers' Company

When we think about printing today, most of us have a few historical references such as Bi Sheng’s invention of porcelain movable type in China during the Song Dynasty (ca. 1040 AD), or the later invention of the metal movable printing press, which led to the Gutenberg Bible printing in 1455. We also often think of printers in Colonial America such as Benjamin Franklin or Thomas Paine. Lesser known however, is the monumentally important Stationers’ Company of London, which fundamentally changed the relationship between writer and audience, controlled publishing for hundreds of years in Europe, and established Anglo copyright law.

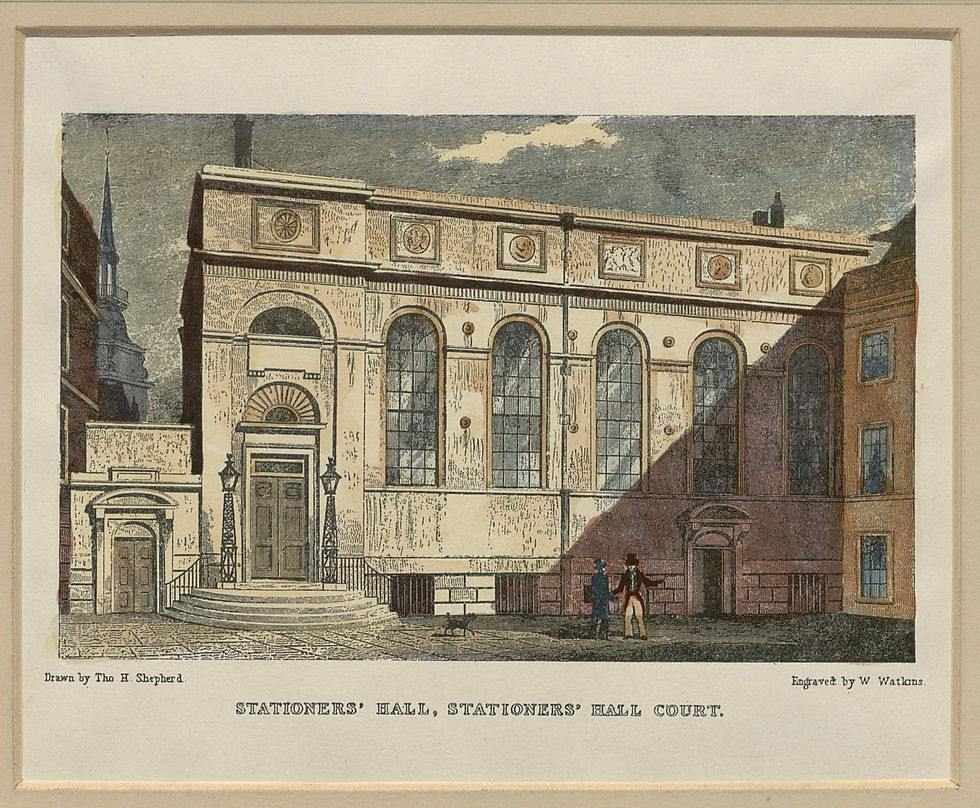

Originally named the Worshipful Company of Stationers & Newspaper Makers, the modern-day Stationers’ Company, existed in some form or another since the 14th Century in London and still exists today. Originally a guild of bookmakers, the Company's hall at Ave Maria Lane, dates back to 1670 and is actually the second location, as the Great Fire of London burned the original building down.[i]

Illustration of Stationers' Hall by Thomas H. Shepherd, Engraved by W. Watkins (c.1700)

What we now know as the Stationers’ Company was formed in 1403, when the guild of stationers, book sellers, book binders and vendors of parchment, quills, and other supplies became very large, producing significant revenue. The 1476 introduction of printing in London added many new printers to the company, and it was given a Royal Charter in 1557, granting them the right to create a livery company in 1559.[ii] The City of London’s Companies are collectively known as “The Livery.” They were first formed in the medieval period as guilds or groups of tradesmen and tradeswomen who joined together to protect, promote and regulate their trades along with the money they could charge. The Livery is composed of 111 companies in London, each representing their own craft or trade.[iii]

Without overstating the presence of women in the livery companies or guilds, it is important to note that they are often incorrectly assumed to be exclusively male; women were present and not specifically barred from membership. During the late medieval period, women played significant roles in the work of guilds generally, and specifically the Stationers’ Company in its early form, even before the organization became an official livery company in 1557. Women could become members and operate within the guild under several specific circumstances which included widows taking over family businesses, the daughters of existing members, and orphaned girls and indentured female servants.[iv]

Widows could eventually become "free" of the Company, meaning they were granted permission to continue their late husband’s business activities within the structure of the guild. Daughters of male members could also join, often by taking over when needed or marrying into the trade. While they might not have had full membership like men, their contributions were crucial to the family business's continuity and success.[v] Finally, orphaned girls could be taken in and apprenticed through the Stationers' Company. These girls were often indentured servants, and trained in various aspects of the trade, such as bookbinding, bookselling, or even managing the business. Once their apprenticeship was completed and the terms of indenture satisfied, some of these women achieved a degree of independence or even full membership, though their roles were often constrained by societal norms.[vi]

The involvement of women highlights the economic and social complexities of early modern guild structures, where family connections and inheritance played essential roles in business operations. Despite the limitations imposed by gender roles and laws of the time, these pathways offered women opportunities to engage in the trade of printing and influence the book industry in London.

While historians access archives to learn about this literary cartel that is now more than 600 years old, there may still be more to understand regarding their overall impact and how they operated in the past. Numerous scholars are still poring over their massive archives to leave no stone unturned. A digital archive of The Stationers’ Company in London (Literary Print Culture: The Stationers’ Company Archive 1554–2007),consists of the following categories of materials:

An archival document from the Stationers' Company, the Company barge, the Company crest.

· The Entry Book of Copies: From 1554 – 1842, this was used to establish copyright, which would belong to publishers, and later to authors until automatic copyright was introduced in 1912. A 1709 Copyright Act meant that these registers became the official record of copyrights.

· The Membership Records, also starting in the 1500s provide invaluable biographical information on printers and publishers, as well as individual members of the Stationers’ Company.

· The Court Records, dating from 1600, are used to understand the inner workings of the company, and are referenced in combination with the Entry Book of Copies to date texts, editions, etc. There are also detailed records of apprenticeship bindings and other internal matters of the various businesses in the guild.

· The English Stock documents, also dating from around 1600, give insight into the publishing arm of the Stationers’ Company, especially the patent system which granted them a monopoly for so long while they held patents on such items as almanacs, psalters, primers, etc.

· Finally, is the section in the archive that contains Photographs & Treasurer’s Vouchers.[vii]

Many notable authors of the Renaissance and Early Modern period had their works published or registered with the Company, often because it was required by law for publishers to register books in order to claim copyright. Here is a short list of some of the most important figures:

· William Shakespeare (1564-1616): Several of Shakespeare’s works were printed by members of the Stationers’ Company, and his First Folio (1623), compiled by John Hemings and Henry Condell, was registered with the Company.[viii]

· Christopher Marlowe (1564-1593): Known for plays like Doctor Faustus and Tamburlaine the Great, Marlowe's works were also printed and circulated with involvement from Stationers' Company members.[ix]

· Ben Jonson (1572-1637): Jonson's collected works were the first to be published in folio format in 1616, reflecting the literary prestige often associated with Stationers' Company involvement.[x]

· Edmund Spenser (1552-1599): The Faerie Queene, one of the most significant poems of the Elizabethan era, was published in association with the Stationers' Company.[xi]

· John Milton (1608-1674): Milton's Paradise Lost (1667) and Areopagitica (1644), the latter a pamphlet opposing censorship, highlight the evolving relationship between authors and the publishing authorities regulated by the Company.[xii]

· Thomas Nashe (1567-1601): A satirical writer and playwright, Nashe's controversial works often drew the scrutiny of the Stationers' Company and regulatory authorities.[xiii]

· Robert Greene (1558-1592): An early English novelist and dramatist whose works were also printed by Stationers' Company members.[xiv]

· Thomas Dekker (c. 1572-1632): A playwright known for his vivid depictions of London life; works like The Shoemaker’s Holiday were registered with the Company.[xv]

· John Donne (1572-1631): A metaphysical poet whose sermons and poetry were published by printers affiliated with the Stationers' Company.[xvi]

· Thomas Middleton (1580-1627): A prolific playwright whose works, such as The Changeling (co-authored with William Rowley), were printed by members of the guild.[xvii]

These authors represent a critical intersection between literature and the early regulation of print culture in London. The Stationers' Company was pivotal in shaping literary dissemination, with many of the period's most important works passing through their hands. Dominating London’s book trade for over 200 years, during the 16th and 17th centuries, the Stationers’ Company eventually lost its monopoly over printing and production but retained a lucrative position in the book through stock in their publishing venture, known as “English Stock.”[xviii]

The role of the Stationers’ Company cannot be overstated in the study of the history of the book, printing and publishing history, copyright history and the workings of a London Livery company. The Stationers’ Company was comprised of a large group of London’s premier printers and publishers, as well as thousands of lesser-known men and women who were printers, publishers, book binders, typefounders, compositors and book sellers. Finally, as we look at the role of women in the workplace throughout history, knowing that women were printers, book binders and business owners going back towards the end of the Medieval period is crucial to our shared history.

Are you excited about printing a project of your own? Start your project on our Start Your Job page.

Notes

[i] "The Stationers’ Company,” Literary Print Culture, The Stationers’ Company Archive, Adam Matthew Digital Ltd, 25 May 2018, https://www.literaryprintculture.amdigital.co.uk/.

[ii] "The Stationers’ Company,” https://www.literaryprintculture.amdigital.co.uk/.

[iii] Paul D. Jagger, “Diversity And Inclusion Among The City and Its Livery Companies,” City and Livery, September 14, 2016, https://cityandlivery.blogspot.com/.

[iv] Maureen Bell, Women in the English Book Trade 1557–1700 (Oxford: Bibliographical Society, 1996), 14–16.

[v] Helen Smith, Grossly Material Things: Women and Book Production in Early Modern England (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), 37–40.

[vi] D.F. McKenzie, Stationers’ Company Apprentices, 1605–1640 (Oxford: Bibliographical Society, 1961), 45–47.

[vii] "Nature and Scope,” Literary Print Culture, The Stationers’ Company Archive, Adam Matthew Digital Ltd, 25 May 2018, https://www.literaryprintculture.amdigital.co.uk/.

[viii] E.K. Chambers, William Shakespeare: A Study of Facts and Problems (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1930), 252.

[ix] Charles Nicholl, The Reckoning: The Murder of Christopher Marlowe (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992), 178.

[x] Ian Donaldson, Ben Jonson: A Life (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), 317.

[xi] Andrew Hadfield, Edmund Spenser: A Life (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), 222.

[xii] Barbara K. Lewalski, The Life of John Milton (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2003), 145.

[xiii] Jonathan Dollimore, Radical Tragedy: Religion, Ideology, and Power in the Drama of Shakespeare and His Contemporaries (Durham: Duke University Press, 2004), 92.

[xiv] Stephen Greenblatt, Will in the World: How Shakespeare Became Shakespeare (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2004), 112.

[xv] Peter Womack, English Renaissance Drama (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2006), 187.

[xvi] John Carey, John Donne: Life, Mind and Art (London: Faber & Faber, 1981), 210.

[xvii] Gary Taylor and John Lavagnino, Thomas Middleton: The Collected Works (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2007), 58

[xviii] “Print, Profit and People: An Exhibition,” The City of London Livery Company for the Communications and Content Industries, The Stationers Company, 12 April, 2018, https://www.stationers.org/company/archive/print-profit-and-people-an-exhibition.

Comments